Napoleon’s secrets revealed in Acre

- Michel Kahn

- May 12, 2020

- 3 min read

In the eastern part of Acre next to the Western Galilee College, you find the smallest French military graveyard in Israel, tombs all shaped and sized slightly different one from the other. The commemoration plate at the entrance, placed by the French Embassy, claims you’re entering Caffareli’s cemetery. Historians agree almost in unison that on this spot Napoleon settled his headquarters on April 1799, at a distance of 1.5 km from the city walls, far enough to be out of shooting range of both the Ottoman and British Artillery.

But when you look at those graves, there is nothing really to indicate that they’re French. Why? Was it so difficult for Napoleon to leave any inscription? A cross? Or some other sign on those tombstones? Didn’t he want us to know that his brave soldiers are buried here? Maybe he had something to hide from us? It gets even more confusing when you compare those tombstones to the ones in the nearby Muslim cemeteries. Their architectural similarity is more than remarkable. Are we dealing here with Muslim graves? When Islam experts furthermore conclude that they all point southwards, in the direction of Mecca, it’s clear that the nail is knocked on those who pretend that we have a Napoleonic cemetery on this spot. Is this an immense fiasco of modern excavation?

In the late 1960s, Acre was still a developing town where Muslims, Christians and Jews lives together side by side till today. The Israeli government decided to promote development in this area by building up an academic institution, the Western Galilee College. Mr. Bernard Dichter, head of town planning in the city, inspected the location and discovered those abandoned graves. Since the law of antiquities is applicable only for artifacts aged before the 17th century, the authorization of Israel’s Antiquities Authority was not opposed to evacuating them.

When Dichter as a civil engineer stares at those tombs again he has a strange feeling that something doesn’t really fit here. There are too many irregularities in order to be a Muslim graveyard. The graves point East – West, and bodies should face south towards Mecca. But all tombs bow between 10 and 15 degrees South and North. A clear, distinctly asymmetric sign, as if somebody wanted to pass a message, a code, something like, I am not who you think I am. He investigated the local villages, and some of them where able to point on the pedestalic tomb, right in the middle, as belonging to “Sheikh Caffari” – that doesn’t sound French either.

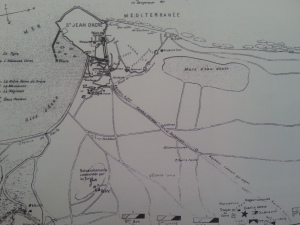

Involved deeply with the history of Acre, he starts looking into the Maps of Jacotin, Napoleon’s cartographer during his Middle East campaign.

He discovers that right on this spot, east of the city close to the aqueduct which provided Al Jezar with water, Jacotin underlined the place with the word “Tombeaux”, graves. Why would he mention “tombeaux” if this was a Muslim cemetery? Dichter was absolutely sure that we are dealing with a well camouflaged French cemetery into a Muslim one. Napoleon knew that when he abandoned the place, the butcher of Acre, El Jazar would destroy every single French remains left behind. This guy didn’t respect anything.

He was so excited about his findings that he invited the French Ambassador, as well as the press, to be present at the excavation of those tombs. One early morning in the summer of ‘ 96 the main, pedestalled tombstone was taken away, under the supervision of the regional doctor. Dichter was yelling with pleasure, as if he got a late Christmas present.

A skeleton missing a feet and arm lay there. No doubt it was the body of the famous French General Maximalien de Caffareli. In one of the battles in Europe he lost his left foot and here in Acre he was shot by an Ottoman sniper in his right arm, amputated and suffered from a deadly infection. He died in the arms of his best friend Bonaparte on 27, April, 1799.

Napoleon buried his body in Acre, but his heart he takes in a silver box with him back to France. Caffareli was eulogized by his soldiers as “father on crutches”. For the members of the “Institue”, 35 scientists and researchers, all gathered under his command he was representing the real values of the Republic – liberty, equality and fraternity. Jacotin was one of them, as well as the famous French Jewish linguist Michel Ventura de Paradis who died a few weeks later from dysentery and is probably buried next to him.

Dichter was deeply impressed that despite his short stay of two months in Acre, the General had managed to carve his personality into the hearts of locals and his memory became immortal by passing from one generation to another as “Sheikh Caffari”.

Napoleon in St. Helena, longing for his friend, unveiled by one golden sentence in his biography written by Doctor Antommarchi why his General’s popularity became a myth during his campaign in the Middle East. “Caffareli loved the glory, but most of all he loved the people”.

Comments